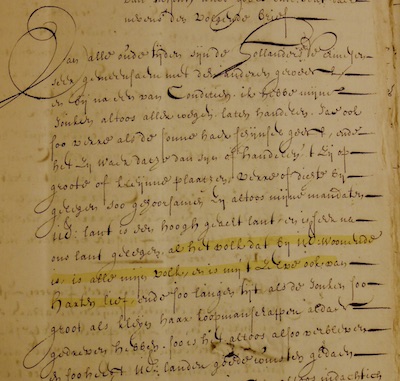

View of Fort Zeelandia

Citation

View of Zeelandia, anonymous, 1644 – 1646, Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-75.470.

The following is an account of one key plank of VOC claims to Taiwan. In this, the VOC representative stresses that the act of accepting protection has resulted in the cession of sovereignty to the Dutch East India Company.

Dagregister gehouden te Edo door Willem Jansz

“Tayouan has about two hundred villages. They lack a chief or a lord and they war constantly with each other day and night. There were five villages in the vicinity of Tayouan and they asked for the protection of the Dutch fort against their enemies. If they received this protection, they would give their land to us and become our subjects. We did as they asked and they acknowledged us as sovereign.”

Citation

5 June 1631, Dagregister gehouden te Edo door Willem Jansz. van Amersfoort, NFJ 271.

Letter from Peter Nuijts to Batavia

“In Hirado, we have learned of the arrival of two Japanese junks out of Taiwan in Nagasaki, and that Pheesodonne (Suetsugu Heizō) has brought sixteen inhabitants from [the village] of Sinkan. The same Pheesodonne gives out that one of these is an ambassador come to see the emperor [shogun] with presents. He has provided them with clothes and has sent an express messenger to petition the councillors [in Edo] that they will be brought there and allowed to see the shogun. They have also, we understand, made great complaints about our procedures on Taiwan.”

Citation

7 September 1627, Letter from Peter Nuijts to Batavia, H. T. Colenbrander and W. P. Coolhaas, eds., Jan Pietersz. Coen: Bescheiden Omtrent Zijn Bedrijf in Indië (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1919–1954), 7.2:1155

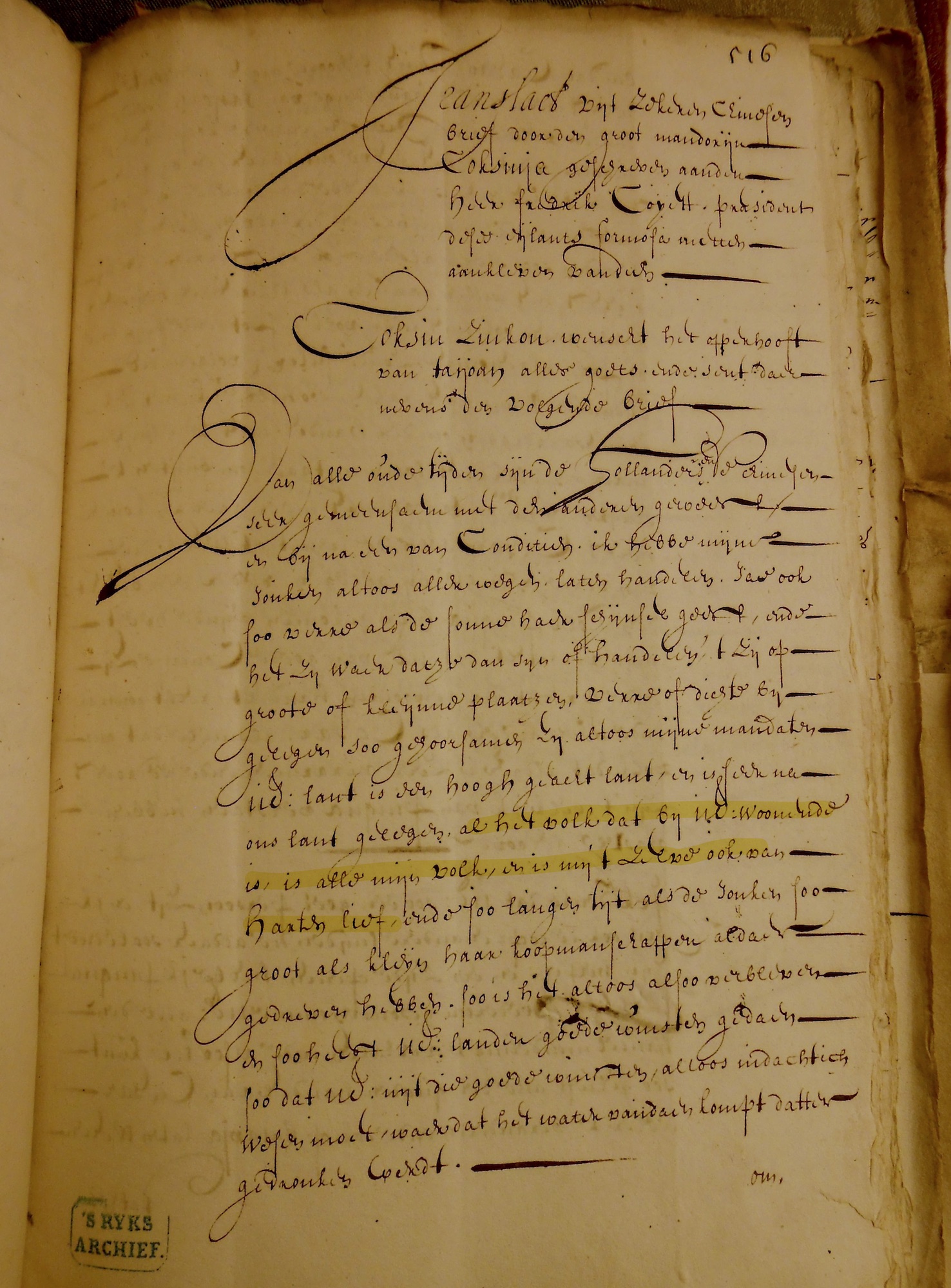

Letter from Coxinga

“all the people that are living [in Taiwan] with you are my people [mijn volk] and they are much beloved by me.”

Citation

Translaet uit zekere Chinesen brief door den groot mandorijn Coksinja geschreven, VOC 1222: 516.

The colonization of Taiwan in 1624 represented the company’s boldest experiment in East Asia and it sent ripples of impact flowing out through the wider region. When the company asserted its authority over incoming vessels, it came swiftly into conflict with Japanese traders, who had already been using the bay for a number of years. The VOC faced an even more dangerous foe in the form of Koxinga and the Zheng maritime organization which eventually ejected the Dutch from their colony in 1662.

The Company Moves Onto Taiwan

View of Fort Zeelandia

While the Company was created to seize control of the rich spice trade of Southeast Asia, it also moved aggressively into East Asia. There, it quickly became clear that the organization’s fortunes depended on gaining access to Chinese commodities. The problem was that Chinese administrators had repeatedly rejected VOC requests for trade. Dutch officials believed they had at last found the solution in 1622 when their forces began to fortify the Penghu or Pescadores islands, which lay in the Taiwan straits between China and Japan seemingly outside the influence of the Chinese state. Rather than going unnoticed, however, the establishment of a small fortress on the Penghus provoked a fierce response from local commanders who massed a fleet to expel the invaders and restore order. Eventually a compromise was reached when the Dutch agreed to retreat to nearby Taiwan, which lay, they were assured, “outside the jurisdiction of China.” In 1624, the Company commenced construction of a stronghold, later christened Fort Zeelandia, on a sandbank in the bay of Tayouan, a key maritime hub that lay on the west coast of the island. From a thin sliver of land, VOC control quickly spilled over to Taiwan proper where the Company came into contact with several thousand Siraya villagers, the members of sub-group within the larger Taiwanese aboriginal population that occupied the coastal plans spread across the southwest of the island.

VOC Claims

Dagregister gehouden te Edo door Willem Jansz

The Company had not initially planned to colonize Taiwan and, lacking clear instructions from their superiors, VOC officials on the ground were forced to improvise claims to possessions to the island. These hinged on two assertions, that VOC rights over Tayouan had been obtained “through a contract with China and because of the consent of the inhabitants themselves.” The contract with China went back to 1624 when the Dutch were ejected from the Penghu islands. According to their story, the subsequent negotiations had produced “a formal contract made with the grandees of China” that allowed the Company “to take possession of Formosa.” Not surprisingly, the reality was far more modest; the supposed formal contract nothing more than an ad-hoc agreement made with the local Ming commander that if the Dutch retreated to Taiwan, he would encourage Chinese merchants to open trade with them there. The issue of local consent was even murkier. The Dutch claimed that nearby villagers had enthusiastically welcomed them when they arrived, thereby handing them rights to the sandbank on which Fort Zeelandia was constructed. In the words of one official, “when we came [to Tayouan] the inhabitants of this land received us in such a welcoming fashion that … they permitted us to construct a fort for our protection, and hence to take possession of this place.” This ignored the reality of a complex relationship with local villagers who alternately embraced Zeelandia as a useful ally while periodically pushing violently back against its expanding influence. The following is an account of one key plank of VOC claims to Taiwan. In this, the VOC representative stresses that the act of accepting protection has resulted in the cession of sovereignty to the Dutch East India Company.

Japanese Counterclaims and Suetsugu Heizo

Letter from Peter Nuijts to Batavia

Beginning in 1625, Dutch officials proceeded to tighten their grip over the bay of Tayouan by placing a tax on all incoming traders, who were required to recognize the Company’s sovereignty over the area as a prerequisite to unloading their goods. Such tactics generated a swift challenge from the port city of Nagasaki and a Japanese maritime entrepreneur, Suetsugu Heizō, whose ships had been trading with Tayouan for years before the Dutch planted their flag there. Furious at the Company’s attempts to assert its authority over a free trading hub, he staged a prolonged campaign designed to undercut the Dutch colonial project on the island. The centerpiece of these efforts was an assault on the Company’s legal claims and in particular on the key plank of its case, that the willing consent of Siraya villagers had transferred territorial rights to Batavia. In 1627, Heizō’s trusted captain, Hamada Yahyoē recruited sixteen Siraya men from the village of Sinkan, a community of a few hundred people located approximately a mile from Fort Zeelandia. They were transported to Japan in an effort to pull Taiwan into the orbit of the Tokugawa shogun.

The Zheng and Taiwan

Letter from Coxinga

As part of his campaign, Koxinga became increasingly interested in displacing the Dutch from Taiwan, which could serve as a secure base from which to continue his struggle against the Qing. Koxinga landed troops on Taiwan but he also deployed his own legal counterclaim to the island. The counterclaim appeared in a range of documents from 1657 onwards but it found its clearest expression in a letter sent to the governor of Taiwan on 1 May 1661 as Zheng troops prepared an assault on the VOC outpost. In this, Koxinga asserted that Taiwan was located close to China and was populated in part by Chinese migrants. It was therefore part of China. How then had how then had Taiwan come into the possession of the Dutch? According to Koxinga, it was the result of misguided generosity on the part of his father, Zheng Zhilong, who had lent it to the Dutch. His troops were thus nothing more than a legal instrument dispatched “to possess and occupy [that], which was only lent to the Company and not given in ownership.”