This is an early source describing how deerskins were used in Japan. Carletti was a Florentine merchant who circumnavigated the world between 1594 and 1606. He stayed in Japan in 1597 and 1598 where he recorded this description of how deerskins were used by Japanese artisans.

Cover of Carletti’s Description of Deerskins

“They also obtain very large numbers of buckskins, which they call sichino caga, and which they prepare in a curious manner, cunningly painting in them with various designs diverse pictures of animals, and other things. And they do this with the smoke from rice straw which colors the entire skin except the part which has been covered with the form of the pictures, which remain impressed and delineated on the white unsmoked part of the skin.”

Citation

Carletti’s Description of Deerskins.

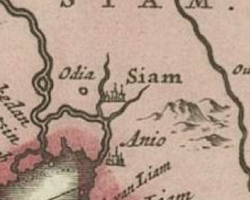

Kleding van Japanners

Citation

Kleding van Japanners, Anonymous, 1600, Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, RP-P-OB-75.407.

Joost Schouten was a Dutch East India Company factor in Japan. He wrote a famous description of Siam that was published in the seventeenth century. In his 1629 letter, he expressed frustration with the Company’s failed attempts to seize control of the deerskin trade. His particular focus was the head of the Japanese, Yamada Nagamasa, whose success in monopolizing the deerskin trade reduced opportunities for the VOC.

Joost Schouten’s Description of Siam

Most years two or at least one [Japanese] junks arrive together with the junk of the Opra or head of the Japanese in Siam … The Opra with good fortune through the capture of the galley of Don Fernando de Silva, the success of his voyages to Japan and now through the succession of the current king has grown greatly in wealth and strength so that now with his or others capital he can send his junk with 3000 piculs of sapanwood and 50,000 deerskins to Japan, which will go along with two smaller Japanese junks … If he succeeds, not only will he pull the trade to him, but it will also cut off the Company’s attempts to resume trade.

Citation

Joost Schouten’s description of Siam.

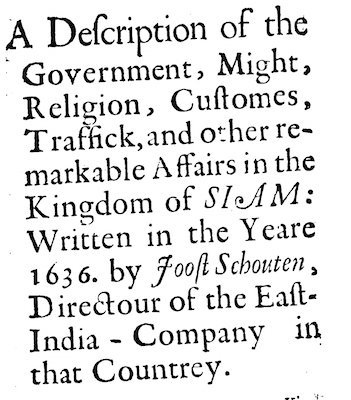

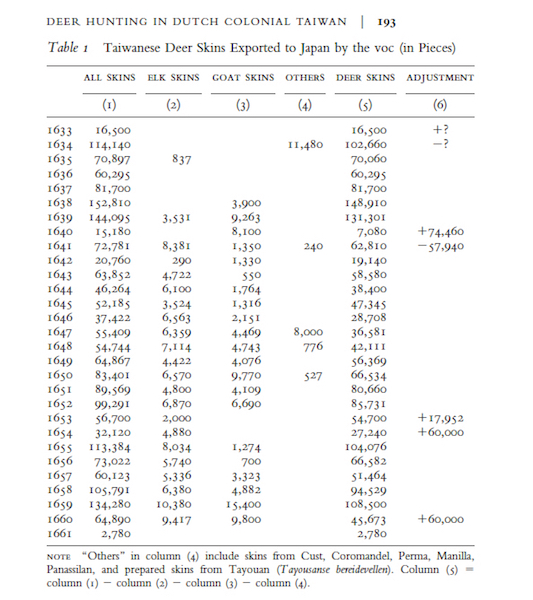

Hui-wen Koo has compiled a meticulous overview of the number of deerskins shipped out from Taiwan during the period of VOC colonization. The table shows that the Company frequently shipped out over 100,000 deerskins. Not surprisingly, the trade had a significant environmental impact on Taiwan, decimating the herds of deer that had once roamed the island.

Deerskins Table

Citation

Hui-wen Koo, “Deer Hunting and Preserving the Commons in Dutch Colonial Taiwan,” Journal of Interdisciplinary History, vol. 42.2 (2011): 185-203.

While deer has been hunted for millennia, seventeenth-century Asia witnessed an unprecedented boom that turned deerskins into one of the most heavily traded commodities across the region. Hundreds of thousands of skins were shipped out each year. Fueling this sprawling trade was a seemingly insatiable demand for deer leather in Tokugawa Japan, which after decades of endemic warfare had entered a prolonged period of stability and economic growth. Across the course of the seventeenth century, the bulk of deerskins came from three places: Cambodia, Taiwan and Siam.

Demand in Japan

Cover of Carletti’s Description of Deerskins

By the early seventeenth century, Japanese society had entered a prolonged period of stability and economic growth after decades of endemic warfare. As Japan prospered, the demand for deer leather, which was softer and more pliable than the available alternatives, grew, spilling over social boundaries. Demand emerged first from Japan’s famed warrior class, the samurai, who prized deer leather for use in armor. But since Japan was at peace after 1600, this armor was employed not in actual battle but for increasingly lavish displays of consumption as long columns of warriors converged on the capital every year as part of the shogun’s new hostage-procession system. While it provided the catalyst, samurai demand alone cannot account for the scale of the trade. Rather in the same ways as Asian textiles and teas gradually filtered down from European elites through different strata of society, so did patterns of consumption for deerskins broaden over time. As Japan’s urban population expanded, the locus of demand shifted from the warrior class to a wider swathe of the population as the inhabitants of Edo, Osaka and a host of castle towns rushed to purchase vast numbers of two-toed socks (tabi), coin purses (hayamichi) and other items made of deerskins. This is an early source describing how deerskins were used in Japan. Carletti was a Florentine merchant who circumnavigated the world between 1594 and 1606. He stayed in Japan in 1597 and 1598 where he recorded this description of how deerskins were used by Japanese artisans.

Japanese Pioneers in Southeast Asia

Kleding van Japanners

In the early seventeenth century, thousands of Japanese migrants and merchants had been propelled by an unprecedented surge in maritime connections into ports across Southeast Asia. The result was the emergence of Japanese settlements (nihonmachi) that sprung up in places like Dilao in the Philippines which had an estimated population of 3,000 Japanese residents, Siam, Cochinchina, and Cambodia. Japanese migrants and merchants played a key role in pioneering the deerskin trade. Japanese merchants in Ayutthaya were instrumental in the development of a new mass trade in deerskins that connected up Japanese consumers and Southeast Asian hunters and merchants. They acted to initiate the trade and formed a formidable competitor to Europeans and the Chinese. Once the maritime restriction edicts prevented them from sending ships directly to Japan, they attempted to maintain grip on the supply and processing of these skins in Southeast Asia. When maritime restriction edicts promulgated in Japan in the 1630s undercut the capacity of the Japanese community based in Southeast Asia to trade directly with the archipelago, Chinese merchants moved to fill the gap they had left. By 1613, the deerskin trade had surged and there are references to 150,000 deerskins shipped from Siam to Japan. They tried to break into the trade, Europeans were forced to sign contracts with the Japanese guaranteeing regular supply of deerskins at fixed costs.

Yamada Nagamasa

Joost Schouten’s Description of Siam

The best known Japanese transplant in Ayutthaya was Yamada Nagamasa, who rose to a high position in the Siamese court. Born in Suruga, Yamada left the service of the local daimyo around 1611 to sail to Siam by way of Taiwan. In the Siamese capital of Ayutthaya, he entered the Imperial Guard where he distinguished himself, rising quickly to become the representative of the Japanese community. After marrying the daughter of a prominent family, Yamada ascended to the highest political rank in Siam. At the height of his power, Yamada commanded a powerful force of Japanese mercenaries, estimated between six hundred and eight hundred. At the same time, Yamada emerged as a driving force in the deerskin trade. According to contemporary descriptions, he dispatched ships carrying as many as 50,000 deerskins to Japan. After the death of the king, however, he was outmaneuvered by political enemies into accepting the governorship of a distant province and eventually murdered in 1630. Joost Schouten was a Dutch East India Company factor in Japan. He wrote a famous description of Siam that was published in the seventeenth century. In his 1629 letter, he expressed frustration with the Company’s failed attempts to seize control of the deerskin trade. His particular focus was the head of the Japanese, Yamada Nagamasa, whose success in monopolizing the deerskin trade reduced opportunities for the VOC.

Taiwan and the Deerskin Trade

Deerskins Table

Recognizing the lucrative nature of the exchange, the Dutch East India Company moved aggressively into this trade after it occupied part of Taiwan in 1624. The Dutch East India Company established an elaborate infrastructure of hunting and licenses on Taiwan. In Taiwan, the Dutch East India Company built a sprawling apparatus capable of funneling tens of thousands of deerskins into its central trading hub on the bay of Tayouan. This enabled the Company to gather tens of thousands of skins each year from Taiwan. In a good year, VOC administrators could ship over 100,000 deerskins from Taiwan, making this a reliable source of income in a world of tight margins. But this extensive hunting came a cost and it triggered severe environmental consequences in Taiwan. In Taiwan, the vast herds of deer that the island was famous for were hunted to such dangerous levels that the trade had to be temporarily suspended. Unlike the fur trade in North America where European hunters were involved in trapping and hunting, the company did not have the resources to dispatch thousands of Europeans into the interior. Instead, it created a comprehensive infrastructure of licenses and protective systems organized around Chinese hunters, who pushed further and further into the interior in search of deerskins. Hui-wen Koo has compiled a meticulous overview of the number of deerskins shipped out from Taiwan during the period of VOC colonization. The table shows that the Company frequently shipped out over 100,000 deerskins. Not surprisingly, the trade had a significant environmental impact on Taiwan, decimating the herds of deer that had once roamed the island.